Ed. note: In an Oct. 29 interview, Capt. Dave Wells said that documents cited in this story were not authentic and denied saying anything attributed to him in the documents. Regarding the specific allegation that he used ebonics, Wells says, "Maybe. I don't know." The authenticity of the documents was verified by the city when it released redacted versions of them, as TYT reported on Sept. 30. TYT stands by its reporting.

Legal documents related to Pete Buttigieg’s ousting of South Bend’s first black police chief describe a plan by white police officers in 2011 to use Buttigieg’s campaign donors to get him to remove the chief, Darryl Boykins, once Buttigieg became mayor.

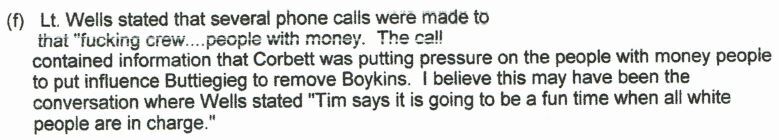

“It is going to be a fun time when all white people are in charge,” one officer is quoted as saying in the documents, which describe secret police recordings. The previously undisclosed documents shed new light on the most controversial chapter of Buttigieg’s South Bend political career.

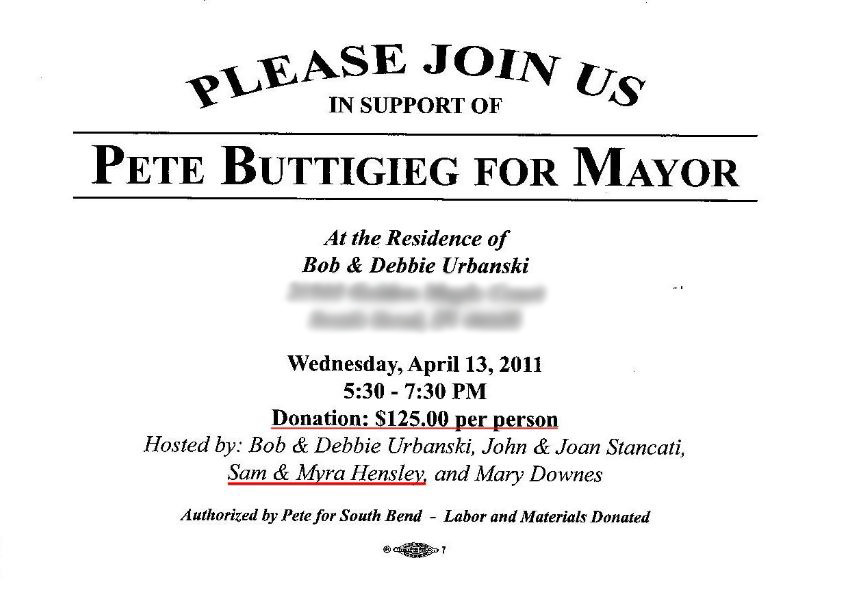

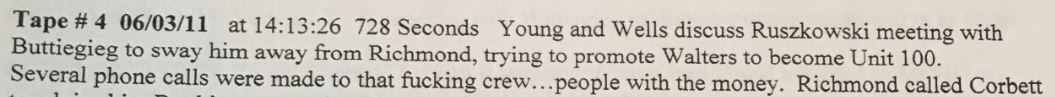

The documents describe a plan to use two Buttigieg donors — including his campaign chairman — to lobby Buttigieg on personnel changes at the South Bend Police Department (SBPD). Both donors deny having such discussions with Buttigieg.

Buttigieg campaign National Press Secretary Chris Meagher asked to see the documents, saying, “You're more than willing to report rumors you are unable to prove, so it'd be nice to see some of this,” but provided no further comment.

The secret recordings of South Bend police phone lines have been a source of intrigue and controversy since their existence was revealed in March 2012, at the dawn of Buttigieg’s mayoralty. Speculation about the recordings and Buttigieg’s refusal to release them has dogged him into his presidential campaign, while their contents have remained largely a mystery.

Buttigieg has said as recently as this year that he wants to know what was said on the recordings, but that he is not sure he can legally even ask the city employee who listened to them to describe what she heard. But the documents show that Buttigieg’s lawyers secretly did just that in 2013.

Lawyers for both Boykins and for Karen DePaepe, the police employee who heard the recordings and was fired for her role in the scandal, would not comment on the content of the documents. Both, however, confirmed to The Young Turks that the city has had a Jan. 4, 2012, Officer’s Report filed by DePaepe that details what she heard, and her written responses to city attorneys who asked her in 2013 what she heard.

The responses the city got include comprehensive, detailed accounts of what is said on the recordings, describing a plan that unfolded over the course of Buttigieg’s 2011 mayoral campaign. Although their accuracy can not be confirmed without listening to the recordings, the documents’ authenticity was confirmed by sources familiar with the matter. (In response to a public-records request, city officials confirmed possession of the Officer’s Report and released a redacted version).

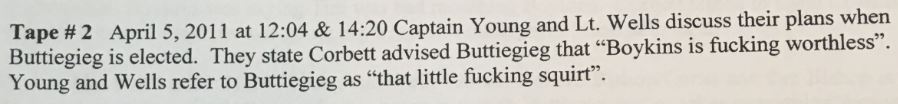

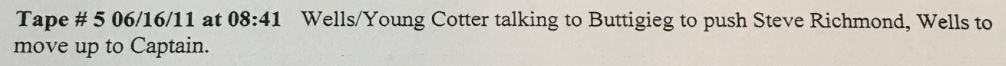

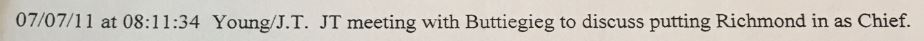

The documents say that, in February 2011, two white police officers were heard discussing a campaign to get rid of Boykins, with Buttigieg donors acting as go-betweens. In April, the officers say they believe Buttigieg is unaware of the plan, and that they expect the “little fucking squirt,” as one calls him, to win the mayoral nomination. After he does win, a third officer in June reports hearing directly from Buttigieg that “Boykins is done.”

The documents indicate that current SBPD Chief Scott Ruszkowski and the current county prosecutor, Ken Cotter, suggested to Buttigieg replacements for Boykins. The documents don’t say whether either man knew about the plan. (Ed. note: After this article was published, an unverified Twitter user identifying themselves as Ruszkowski denied even speaking with Buttigieg until 2013.)

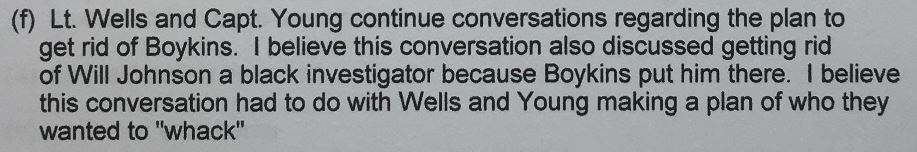

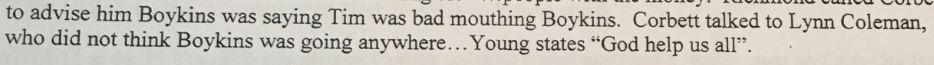

Some of the officers involved — from both the SBPD and the county homicide unit (made up of police from South Bend and its suburbs) — allegedly discussed Boykins in racist terms, using ebonics in reference to him and other black people. Two black police officers are named as either a target for removal or the subject of racist rhetoric.

At some point in January 2012, his first month in office, Buttigieg learned that SBPD police had secretly been recorded by the department and that the FBI was investigating for potential violations of federal wiretapping laws. Two months later, Buttigieg told Boykins to resign. After black South Bend leaders sided with Boykins, Boykins rescinded his resignation. On March 30, in the face of the black community’s outrage, Buttigieg instead demoted Boykins from his position as chief — allegedly for his handling of the recordings.

Less than two weeks later, April 10, 2011, Buttigieg fired DePaepe, the SBPD director of communications who discovered the calls, reported them to Boykins, and then transferred excerpts to five cassette tapes. DePaepe went public almost immediately, reportedly suggesting that the tapes revealed possible police wrongdoing, including racist rhetoric.

It was DePaepe who first suggested that the tapes for which Buttigieg demoted Boykins might reveal a plan to accomplish exactly that.

In her 2012 wrongful-termination suit, DePaepe refers to a plan to get Buttigieg to oust Boykins — but gives no details. Since settling their suits against the city, and facing possible lawsuits themselves, DePaepe and Boykins have refused to speak publicly about the recordings.

For seven years now, the battle over the tapes has divided and defined South Bend. Buttigieg’s refusal to release them, claiming legal restraints, has cemented them as a subtext of virtually any discussion about the city’s police, its black community, or its power structure.

The following account of what was said on the recordings is drawn from documents including internal SBPD reports filed in January 2012 and DePaepe’s responses to the city’s December 2013 interrogatories.

The story told by the documents includes specific details and allegations regarding multiple individuals, some of whom have never been publicly tied to the recordings. Unless otherwise noted, those named in this account declined to comment or could not be reached.

Fixing a Ticket

It all began with an alarm from the SBPD’s Dynamics Instruments Reliant Recording System.

The system was supposed to back up digital audio recordings of SBPD phone lines automatically. When the system froze, DePaepe began checking the recordings. On February 4, 2011, noticing that the voice on one call didn’t match the officer assigned to that line, DePaepe listened to more calls, to determine whether the recording system had malfunctioned.

DePaepe didn’t realize it, but Captain Brian Young had gotten a new phone line from another officer who had just been promoted. And Young didn’t know that he had just inherited a phone line that was being automatically recorded. (In the Jan. 2012 Officer’s Report, DePaepe writes that a previous chief ordered numerous lines be recorded to capture calls alleging officer misconduct.)

Over the next several months, the recordings, according to the documents, tell a story involving some of the most powerful players in South Bend politics. But the trail started with a single ticket for a seat-belt violation: A ticket that Captain Young tried to fix.

The ticket had been issued in neighboring Mishawaka to the wife of an SBPD SWAT team member, and Young had emailed county prosecutor Eric Tamashasky in December 2010 to make it go away.

Capt. Young tells Tamashasky the ticket was never taken care of and her license was suspended, which Tamashasky says he will also fix. DePaepe gave her account of what happened next in her interrogatory responses.

“Young then asked what would happen if [Indiana State Police] stops the officer’s wife and arrests her for driving on a suspended license, to which Tamashesky [sic] replied 'we’ll fix that too'. Both Tamaskesy and Young then laughed about it.”

When DePaepe listened to more calls to find out what happened with the ticket, she stumbled onto something much bigger. This time, it was a conversation between Young and then-Lt. Dave Wells, of the county homicide unit, that began with a black street gang but led to the SBPD’s black chief. According to DePaepe:

“They were discussing problems with a local gang known as the Cashout boys when Lt. Wells started speaking in what is termed as ebonics, when a person mocks or mimics the way a black person speaks. Lt. Wells in ebonics stated to the effect ‘ain’t nothin gonna get done with the Cashout boys cuz Boykins, he take care of his home boys.’...

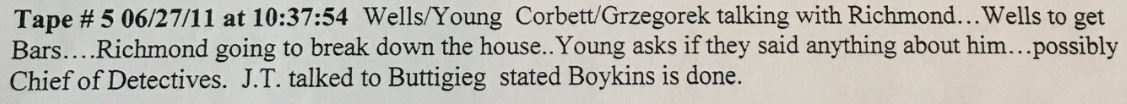

“Both Wells and Young began to ridicule Boykins and mock him, when Wells stated that Corbett had a plan to get rid of him.”